Standing outside the ALB1 Amazon Fulfillment Center in Schodack, NY, surrounded by supporters holding signs reading “Union Strong!” and “Protect All Workers,” Heather Goodall—president of the nascent ALB1 unionization effort—spoke out against violence inside Amazon warehouses.

“We are organizing this union to put an end to the abuse,” said Goodall. “We will not tolerate any more deaths at the hands of Amazon.”

Organizers were gathered to honor the life of Rafael Reynaldo Mota Frias, a 41 year-old man who died from a fatal heart attack at a New Jersey Amazon warehouse this past Prime Day. According to coworkers, Frias complained of chest pains for nearly an hour before management called emergency services. Goodall said that company negligence, in tandem with grueling labor conditions, were to blame.

Since May, Goodall has gathered a team of ALB1 Amazon employees to build worker power, with the ultimate goal of unionizing the warehouse this summer. Through unionization, the group hopes to address the kinds of safety concerns that organizers say contributed to Frias’ death.

The burgeoning effort to unionize ALB1 was recently endorsed by the historic Amazon Labor Union (ALU), an organization of Amazon workers aiming to unionize company warehouses across the nation. The ALU gained its first groundbreaking victory this April, when workers at the JFK8 warehouse in Staten Island voted yes to unionization. This win marked the first successful union organizing campaign in Amazon’s history.

The campaign at ALB1—now officially ALB1 ALU Local 2—could be the second.

Goodall, speaking from personal experience, says that unionization is a matter of life and death for workers inside Amazon’s warehouses.

On July 2nd, while retrieving an item from a rack 20 feet in the air, a heavy box fell onto Goodall’s forklift, nearly striking her. Shaken, she went to Amcare—Amazon’s on-site emergency services—where a worker read her blood pressure at a highly dangerous 210/170 and immediately called 911.

Goodall says she diligently communicated her health concerns with supervisors, requested transfers to less strenuous positions, and applied for a role in HR to avoid stress on her heart. She says that her requests for accommodation were ignored.

“I almost died in that warehouse,” she recalled.

For months, Goodall and other workers have been demanding that management shut down the warehouse’s many dilapidated “pick aisles”—racks where the company stores merchandise—for much-needed repairs. Andre Beaupre, another ALB1 worker and Vice President of the union campaign, described the aisles as “completely destroyed,” with heavy boxes falling through frames, putting workers at risk of head injuries and crushed or broken limbs.

Beaupre has managed to avoid working in the pick aisles by packing boxes and training for the loading dock. “I won’t do picking,” he told Albany Proper. “I don’t feel like risking my life is worth the money Amazon pays.”

Rather than closing down dangerous aisles to make them safer for workers, organizers say, Amazon has increased inventory at ALB1, overstuffing shelves and bins with more items than the warehouse was built to hold. Workers like Goodall and Beaupre see this inaction as further evidence that the company prioritizes production over employee safety: to Amazon, reducing inventory or shutting down parts of the warehouse for repair is more costly than replacing injured employees.

The company’s “profit over people” agenda has made working at warehouses like ALB1 increasingly dangerous, workers testify, at the same time sparking support for unionization efforts.

Tia Leanza started working at ALB1 in September after realizing she could make slightly more money than she had as a Head Start educator. Leanza said that she soon realized that, at Amazon, your “rate”—the speed at which a worker can pack boxes, lift items, etc.—is “more important than anything else.”

As a packer, Leanza is expected to assemble and pack 60 boxes per hour, standing at a conveyor belt for 9 hours a day. If she takes a bathroom break or stops to stretch, she says, the computer that monitors her work pace begins to accumulate “time off-task,” a metric that ALB1 managers can use to reprimand or even fire employees.

This breakneck pace is exhausting to maintain, workers say. Quotas can also create a work environment in which small but dangerous mistakes are commonplace. At ALB1, an XL warehouse that deals with packages exceeding 50lbs—including heavy appliances, TVs, and furniture—a mislabeled or poorly taped box can lead to serious injury.

“I’m not a fast packer by any stretch of the imagination…the highest I’ve gone is 45 boxes an hour,” Leanza said. “But, I can guarantee that my boxes have heavy labels so somebody down the line isn’t pulling out their shoulder or messing up their back because I didn’t give them forewarning.”

By setting impossible quotas and celebrating quick but shoddy work, Amazon deprioritizes worker safety in its warehouses. As a result, Leanza’s efforts to consider other worker’s safety on the packing line could be penalized. She might even be replaced with faster, less experienced packers.

According to a report from New Yorkers for a Fair Economy, ALB1 has a serious injury rate of 19.8 per 100 full-time workers. This means that for every five workers in the warehouse, one worker has been seriously injured resulting in lost time or restricted duty.

“We’ve had over one hundred EMS arrivals at the facility in a year and a half,” Goodall told Albany Proper. “I took the job in February, and by March I was injured twice. In April I was out for three weeks with COVID.”

Within a week of working at the warehouse, Goodall says, she could tell that workers needed a union to address the health and safety concerns, among other abuses. After Amazon cut COVID pay for US workers at the beginning of May, just weeks after Goodall herself had fallen ill through an exposure at the warehouse, she began organizing in full force.

“I came back from COVID and saw signs hanging on the HR wall that said ‘no COVID pay, no excuses,’” she recalls. “I thought, this has to be a joke, right? I knew they were breaking the law.”

Ultimately, Goodall was right. By NYS law, Amazon—with 39,000 employees across NY and an annual income of 33.364 billion dollars—is required to provide at least 14 days of COVID pay to workers under state quarantine orders.

After taking down several signs, Goodall filed a complaint with the New York State Department of Health and the Attorney General’s Office. She spoke out to her co-workers, encouraging them to stand up to warehouse managers and HR officers who refused them COVID pay. Across the warehouse, people heard her message: “Educate, empower, encourage, and stand up to Amazon.”

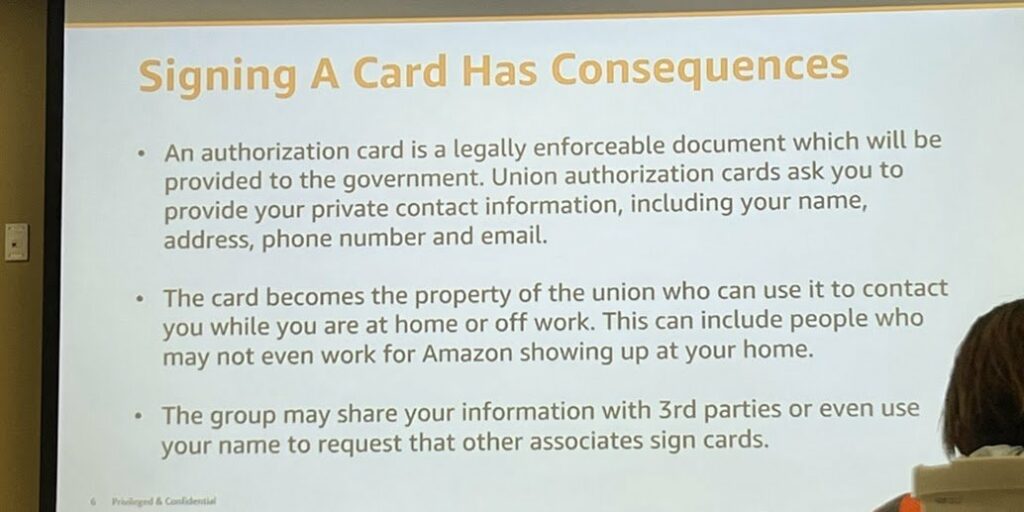

Photos provided that show union-busting messages displayed at ALB1.

At this stage, ALB1 ALU Local 2 is collecting union authorization cards to submit to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Organizers must gather cards from 30% of warehouse workers before the NLRB will approve a union election. This is no easy task, especially for organizers working full time: ALB1 employs nearly 1,000 people, with shifts running around the clock.

“Right now, we’re collecting 33 signatures a day,” said Goodall. “We’ve already hit 30%, but we’re aiming for 80%. We want to get the word out as much as possible.”

Amazon is working hard to shut down the campaign. The company is known for engaging in illegal union-busting tactics, quelling many efforts to unionize workers over the years in other warehouses.

At ALB1, warehouse management recently posted signs explicitly telling workers not to sign union cards. When the campaign posted flyers clarifying their efforts to gather signatures, this information was promptly removed and replaced with more anti-union propaganda, says Andre Beaupre.

On July 26th, ALB1 management also began holding “captive meetings” in which employees are required to listen to anti-union scare tactics and misinformation about the legal implications of unionization. Administrators even called the police on organizers for sharing information regarding the unionization campaign with co-workers.

Tia Leanza said she is optimistic that workers will be able to see through the company’s attempts to intimidate workers.

“If you’re going to spend so much money on union-busting, then clearly you’re afraid of worker power,” she said. “They’re clearly very scared.”

Goodall echoed Leanza’s sentiments, saying that the ALB1 union effort is set to make history and change people’s lives.

“We won’t stop until Amazon listens,” she said. “They are eventually going to have to concede.”

Here’s what community members can do to help the ALB1 unionization efforts:

• Send messages of support to alb1voicesunited@gmail.com.

• Encourage Governor Hochul to sign the Warehouse Workers Protection Act.

• Curb your Amazon spending and donate to union funds.

• keep updated on what’s going on inside your local facilities.

- Inside the fight to unionize Amazon’s ALB1 – August 2, 2022